Canal Olympia Bows Out

Whenever I am asked about my master’s course, I know immediately there will be a follow-up question.

I just finished my Master’s in Creative Industries and Art Organisations at Queen Mary University of London. To most people, it sounds very broad. Indeed, sectoral studies are broad, but in this case, I do not think I can summarise a year of study and 10,000 words of my dissertation in a few lines. What I can say is that the course has completely reshaped my view of the state of the creative industries in Cameroon.

Because I have nothing much to do, it may seem strange that I would commit hours weekly or bi-weekly to writing articles that people might not read. But I am burdened with a quest for knowledge. I need to understand the why and the how. This reflective column I am starting, which I call Cultural Commentary, is dedicated to reshaping the perspectives of those who care to read about a sector they entered with expectations that are currently not being met. I will begin with the film, cinema, and audiovisual sector because it is what I am most passionate about, among others like literature, digital media, music, and fashion, which I might explore later. This is not a news or entertainment blog chasing clicks, so I will not focus on trends.

Speaking of trends, Canal Olympia Bessengue has bowed out of the cinema business in Cameroon. This should be trending, but who cares? After all, those who truly love movies now have access to shared Netflix accounts and pirated films on Telegram. Nine years ago, when Canal Olympia opened its 300-seater indoor theatre on the campus of the University of Yaoundé I on 16 June 2016, I believe I was preparing my application to the Department of Performing and Visual Arts at the University of Bamenda, excited about learning film. Who would have thought that a project backed by France’s Vivendi Group Chairman, Vincent Bolloré, announced as being inspired by “Cameroon’s leadership to revive cultural life for youths,” would end this way?

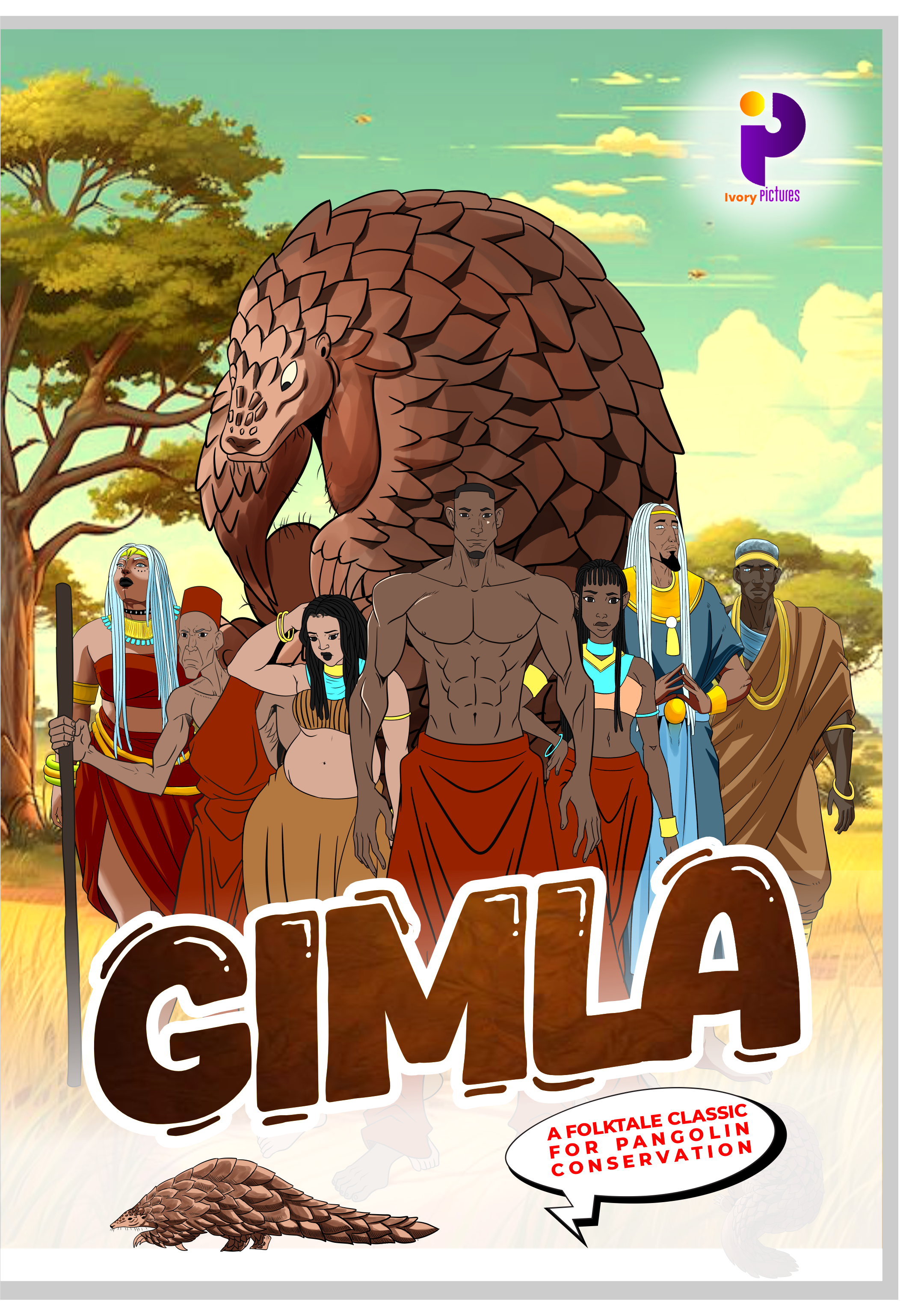

I often wonder what it felt like to watch a movie in a cinema. I would not know, as my hometown, Bamenda, did not have one at the time and still doesn't. My first cinema experience was at a Canal Olympia screening of Saving Mbango by Nkanya Nkwai, and I must say, it was great. (Image above)

This takes me back to the 1990s, not from experience, as I was a toddler then, but from study. It was a time when Cameroonian filmmakers made it to the Cannes Film Festival, the era of Jean-Pierre Bekolo. The causes of the closure of cinemas have been linked to many factors, from economic crisis to government focus on building national television networks such as CRTV, among others, reasons you can easily find through a simple Google search.

But this is 2025. Canal Olympia has stated some incremental factors backing their decision to leave us hanging, or might I say, to avoid becoming bankrupt by accepting a buyout. A smart business decision? Canal Olympia says Cameroonians find it difficult to spend 2–3 dollars out of pocket for cinema, resulting in relatively low attendance. What does this say about the economy? I am particularly worried about the cultural factors. Are we lacking a cinema culture? And why is it so difficult to build one? Culture, being shared beliefs and values of a people, has characteristics of repetition. Once it stops, especially considering a two-decade gap, rebuilding becomes a serious issue.

If you have read this far, when was the last time you went to the cinema, and why did you go? Again, it must be exhausting at this point to read anything about Cameroon without the government receiving some blame. Legitimately so, of course, when there is little or no incentive to support the cinema business or the film sector entirely. Yes, I did call it a sector, because I do not think we have met the criteria of being an industry.

At this point, it is important to note that the film, cinema, and audiovisual sector is not a priority to the government, considering that the Ministry of Culture is one of the least funded ministries, yet expected to cater to over eight creative sectors alone. Talking about bowing out after nine years, how about just two years? In this case, the Nigerian cinema chain Silverbird wins the record. They packed up and left the Douala Grand Mall by 2024, after launching in 2022.

In my reflections, I often wonder how we can rebuild our broken cinema culture. What about local council halls left unused, repurposed for community screenings? Prioritising Gen Z, but will they even be interested now that there is TikTok? How do we get them from their phones into a cinema hall?

In my lamentations about the lack of a cinema hall in Bamenda, and the frustrations of screening locally made films in spaces meant for theatre, such as the Alliance Française hall, I remember a friend, a filmmaker and activist, once shared with me his attempt a few years ago to advocate for the use of the 500-seater hall filled with coffins at downtown Bamenda, towards the cathedral. He was locked up in a cell at Up Station. There goes the fear of politics.

As we await revelations about the plans of the new owners of the Canal Olympia cinema structures, there may be hope. But the sale also feels like a setback. What do you expect will change?

I never did apply for admission to the Department of Performing and Visual Arts. I made a U-turn into Communication and Development. At the time, it was a mandatory decision, but today I believe it was the right one, cementing my background in development entirely.

In my next Cultural Commentary, I will dissect why filmmakers and other creatives are moving abroad, and what this means for the creative sector.

by Evita Afungfege (Chief)